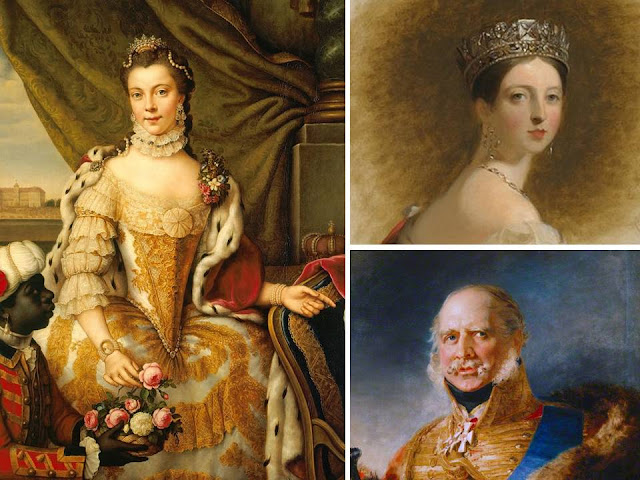

In 1837, King William IV died and the crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain passed on to his niece, Princess Victoria of Kent. She was the only child and heir of the king's younger brother, Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent, who met his untimely death in 1820. The reign of the new queen meant the end of the personal union of the British and Hanoverian crowns, which had been united since King George I inherited the British throne in 1714 after the death of Queen Anne. Salic Law, an ancient law which forbids females from dynastic succession and imposed in German principalities and kingdoms, barred Victoria from succeeding to the throne of Hanover. As such, the throne of Hanover was inherited by her uncle, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. This ended more than 120 years of personal union of the two crowns.

Immediately after inheriting the crown of Hanover, conflicts ensued between the uncle and niece. Among others, King Ernest refused to give up his apartments on St. James’s Palace, which, according to Edgar Sheppard in Memorials of St.James's Palace volume 1, the king "retained for years, but were left unoccupied" and "it seemed improbable that he would ever occupy them again." The suites had been granted to him by his father, King George III "for life." Sir Charles Greville later noted that several attempts to have the king give up his apartments were met with “flat refusal.”

He also refused to let Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Queen Victoria’s husband, take precedence over him. In her book Queen Victoria: Her Life and Times, 1819-1861, Cecil Woodham Smith wrote that the Hanoverian king used his influence over the Tories to object the passage of the Act of Parliament that gave the prince the precedence over the princes of the blood royal. (see also Greville Memoirs)

The most controversial conflict between the two monarchs arose over the jewels of Queen Charlotte, King Ernest’s mother and Queen Victoria’s grandmother. The jewels in question were divided into two parts. The first were those jewels, which came from King George II. According to Sir Charles Greville these gems were “undoubtedly Hanoverian.” The second part were the once bought by King George III and given to Queen Charlotte as a wedding gift. These, Cecil Woodham Smith explained, “were bought with English money and, in the opinion of the English people, to call them the Hanoverian crown jewels was ridiculous.” When Queen Charlotte died in 1818, she willed these jewels to the House of Hanover. The dying queen must have thought that the British Crown would remain within the male heirs of the House of Hanover forever. The jewels successively passed on to King George IV and King William IV but the issue of who should possess these precious gems came about when King Ernest Augustus succeeded to the Hanoverian throne.

But Queen Victoria would not surrender without a fight, considering that the value of these jewels were worth a fortune. The young queen was also fond of these jewels, especially the necklace which “was reputed to be the finest rope of pearls in Europe.”

Sir Charles Greville, writing in his Memoirs, had presented a detailed narrative of this protracted case:

"The late King of Hanover on the death of William IV claimed these jewels upon the ground that they were partly belonging to the Crown of Hanover and partly had been bequeathed to him by Queen Charlotte. Our Government, on behalf of the Queen, naturally resisted the claim. After a good deal of wrangling they were at last prevailed on to name a commission to investigate the question, and Lord Lyndhurst, Lord Langdale, and Chief Justice Tindal were appointed accordingly. After a considerable delay and troublesome inquiry, they arrived at a conclusion, but when they were just about to give their award Chief Justice Tindal died. Lyndhust and Langdale were divided in opinion, no award could be given. Then Chancellor, Lord Cottenham, refused to renew the Commission, and the matter has stood over ever since.”

Lord Lyndhurst confessed to Greville of the difficulty that they encountered "to make out whether the jewels which Queen Charlotte had disposed of by her will had really been hers to leave, or whether she had only had the use of them." It only became certain that the jewels in question were actually the late queen's when the arbitrators discovered the will of King George III who "expressedly left them to her."

A December 23, 1857 article in the Times of London speculated on the value of the jewels: "As the jewels thus claimed are supposed to be worth considerably more than 1,000,000 pounds, a single stone having cost nearly 20,000 pounds, they were not to be relinquished without a struggle; and I am assured that every possible expedient was resorted to in England to baffle the claimant."

However, according to Greville, the value of the jewels "has been enormously exaggerated, but is still considerable." According to Lord Lyndhurst, they were worth 150,000 pounds.

Queen Victoria, who held custody of the jewels at that time, insisted that they belonged to the British Crown, a claim countered by her uncle who maintained that they should go to the male heir, who was himself. Queen Victoria also mocked her uncle by wearing the jewels in every opportunity she could. The incensed king wrote to his friend Lord Strangford, "The little Queen looked very fine, I hear, loaded down with my diamonds." King Ernest Augustus died in 1851 without getting his mother’s jewels but his son and successor, King George V, continued the case.

According to the Times:

“Ultimately, in the lifetime of the late King, the importunity of the Hanoverian Minister in London drove the English Ministry of the day to consent that the rights of the two Sovereigns abroad should be submitted to a commission composed of three English judges; but the proceedings of the commission were so ingeniously protracted that all the commissioners died without arriving at any decision; and until Lord Clarendon received the seals of the British foreign office all the efforts of the Court of Hanover to obtain a fresh commission were vain. Lord Clarendon, however, seems to have perceived that such attempts to stifle inquiry were unworthy of his country, for he consented that a fresh commission should be issued to three English judges of the highest eminence, who, after investigation, found the Hanoverian claim to be indisputably just, and reported in its favour.”

Finally, in 1857, with a new set of arbitrators, a decision was finally reached. “In the present year [1857], however, the Government thought the matter ought to be decided one way or another, and they issued a fresh Commission, consisting of Lord Wensleydale, Vice-Chancellor Page Wood and Sir Lawrence Peel (ex-Indian judge), and they have given judgment unanimously in favor of the King of Hanover,” Sir Charles Greville recorded.

Before the year ended, the arbitrators decided in favour of Hanover. The decision “desperately annoyed Queen Victoria”, but it also disappointed her Hanoverian cousins who were hoping to receive financial compensation instead. Queen Victoria handed over only a few items to her Hanoverian cousins, since "some few seem to have been allotted to the Queen." Among the jewels that she gave to the Hanovers were Queen Charlotte’s small diamond nuptial crown and a few other diamond pieces. The pearl strand remained with her since her cousins gave up their claim on the item. She also had the court jeweller make duplicates of the pieces which she liked the best. When she died in 1901, she left these pieces to the Crown and they now form part of the British Crown jewels.

.png)

0 Comments