|

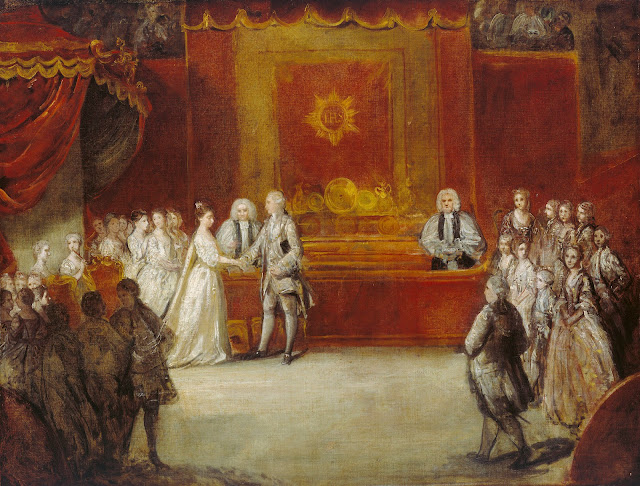

| The Marriage of George III 1761 by Joshua Reynolds, 1761. |

“When King George III succeeded to the throne of England upon the death of his grandfather, George II, it was considered right that he should seek some lady in marriage who should fulfil all the duties of her exalted position in a manner to satisfy the feelings of the country at large, and at the same time those of a Prince so ardent an admirer of the fair sex as was George III,” writes Charlotte Papendiek* in her extensive memoirs.

The choice for a bride fell on the 17-year-old Charlotte of

Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The decision was reached primarily because, having been

raised in a small German duchy and being the daughter of the Prince Mirow, the

younger brother of the reigning duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the princess was

thought of as not having the experience or the interest to meddle in politics.

In July 1761, King George III sent for an entourage to

escort his would-be bride from Strelitz to London. The party consisted of the Duchess of Ancaster

and the Duchess of Hamilton, who served as the would-be-bride’s ladies of the bedchamber; Mrs. Tracey, bedchamber woman; Earl Harcourt, proxy for the king ; General

Graeme, to conduct the whole escort ; and Lord Anson, commander of the

squadron. George and Charlotte were

married by proxy, their marriage contract signed by Charlotte’s brother,

Adolphus Frederick IV (who inherited the duchy from uncle Adolphus Frederick

III) and by the Earl Harcourt, representing the king. The people of Strelitz

rejoiced with the union, the festivities running for three days before the bride and her party

departed for London on August 17.

After a stormy crossing of the English channel, the party reached

Harwich on September 7. They rested the night in Witham, at the residence of Lord

Abercorn, and arrived at 3:30 pm the next day at St. James's Palace in London.

On this big day, Papendiek writes:

“They entered London by the suburb of Mile End, and passing through

Whitechapel, which could not have given the strangers a very promising idea of

the beauty or grandeur of the metropolis, or the Princess a very exalted notion

of the people over whom she had come to reign (for that was at that time, as it

is now, one of the most squalid and dirty quarters of London), they continued

along the New Road to Hyde Park, which they crossed, and thence down

Constitution Hill to St. James's Palace, where the King then resided. His

Majesty, surrounded by his brothers, received his bride at the small private

garden gate, in the Friary, and led her through the garden, up the flight of

steps to the Palace.”

The queen, still weary and tired from the long trip, was

married to King George III that very night.

“At about ten o'clock the procession entered the Royal Chapel,” writes

Papendiek. Charlotte was led to the altar by the king’s brothers, the Duke of York

and Prince William, while she was given away by the Duke of Cumberland. Ten

bridesmaids attended her. They were Lady Sarah Lennox, Lady Caroline Eussell, Lady

Caroline Montagu, Lady Harriot Bentinck, Lady Anne Hamilton, Lady Essex Kerr, Lady

Elizabeth Keppel, Lady Louisa Greville, Lady Elizabeth Harcourt, and Lady Susan

Fox- Strangways. Dressed “in Court robes of white and silver,” they bore the

bride’s train “of purple velvet, lined with ermine, the rest of her dress being

of white satin and silver gauze.” The Archbishop of Canterbury officiated the solemn

ceremony.

Horace Walpole later wrote: “The Queen was in white and

silver ; an endless mantle of violet-coloured velvet, lined with ermine, and

attempted to be fastened on her shoulder by a bunch of large pearls, dragged

itself and almost the rest of her clothes half- way down her waist. On her head

was a beautiful little tiara of diamonds ; a diamond necklace, and a stomacher

of diamonds, worth threescore thousand pounds, which she is to wear at the

Coronation, too.”

King George III presented her bride with a fortune’s worth

of gifts, including “a pair of bracelets, consisting of six rows of picked pearls as large

as a full pea ; the clasps — one his picture, the other his hair and cypher,

both set round with diamonds ; necklace with diamond cross ; earrings, and the

additional ornaments of the fashion of the day.” She also gave her “a diamond

hoop ring of a size not to stand higher than the wedding ring, to which it was

to serve as a guard.” Queen Charlotte never adorned the finger where this ring

was snuck with any other ring or jewelry.

When the ceremony ended, the couple proceeded to their apartments. Queen Charlotte, feeling fatigued from the lengthy and strenuous travel, excused herself from attending the

banquet after she and her husband welcomed the guests. Instead, a private supper was served to

the king and queen alone.

Charlotte Papendiek* served, first, an assistant keeper of the queen's wardrobe and later, her reader.

She was the daughter of Friedrich Albert, who was the queen’s page, barber and

hairdresser. In 1783, she married Christopher Papendiek, court musician to King George III. In 1833 Charlotte

Papendiek started writing an extensive set of memoirs, although they were left

unfinished. Her granddaughter, Augusta Anne Arbuthnot, published them in 1887.

.png)

0 Comments